St. Louis Cultural History Project—Spring 2019

Charles M. Charroppin, S.J and Assistants

Two Jesuit Photographers:

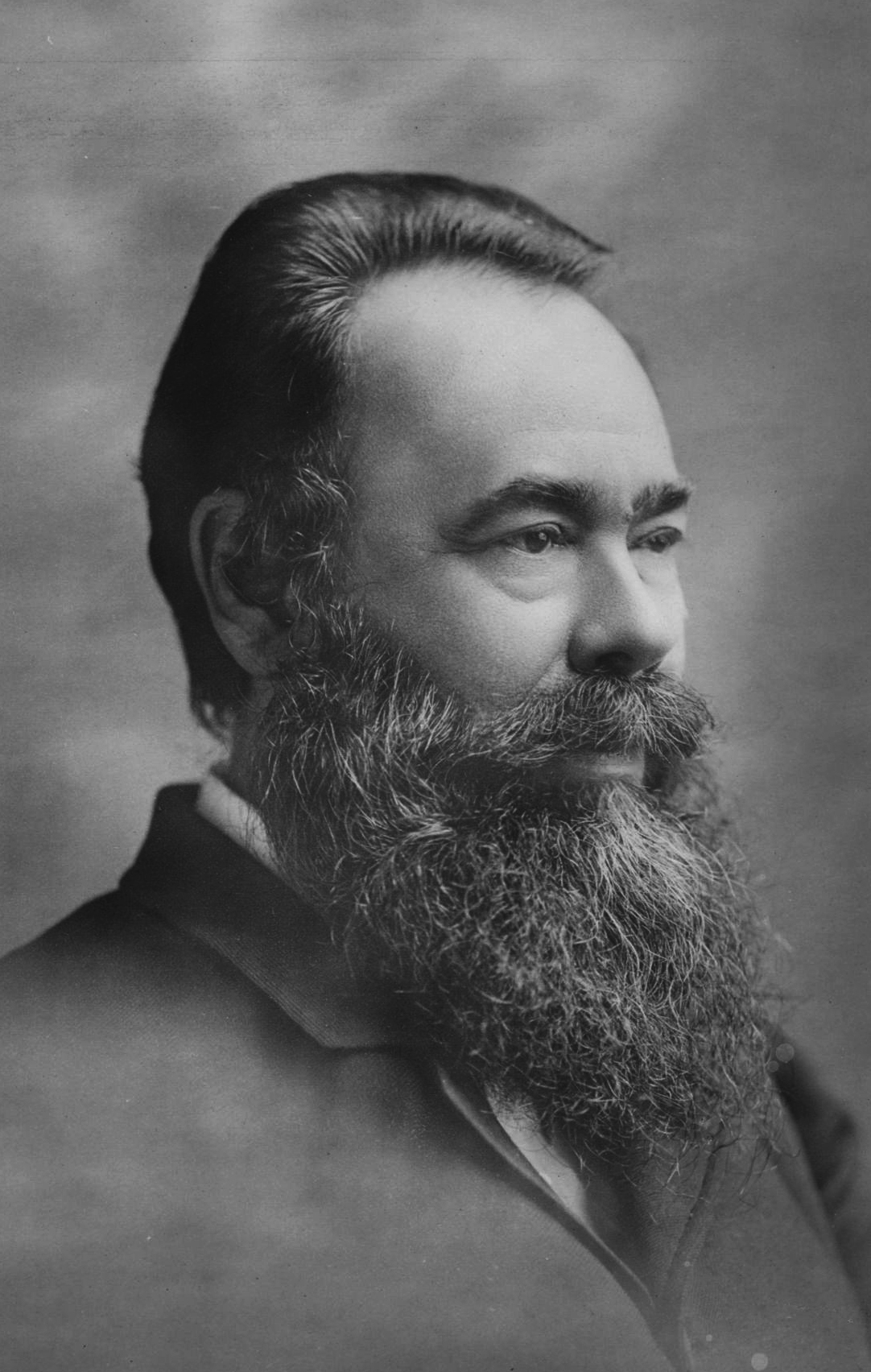

The Quaint Genius,

Charles M. Charroppin (1840-1915) and

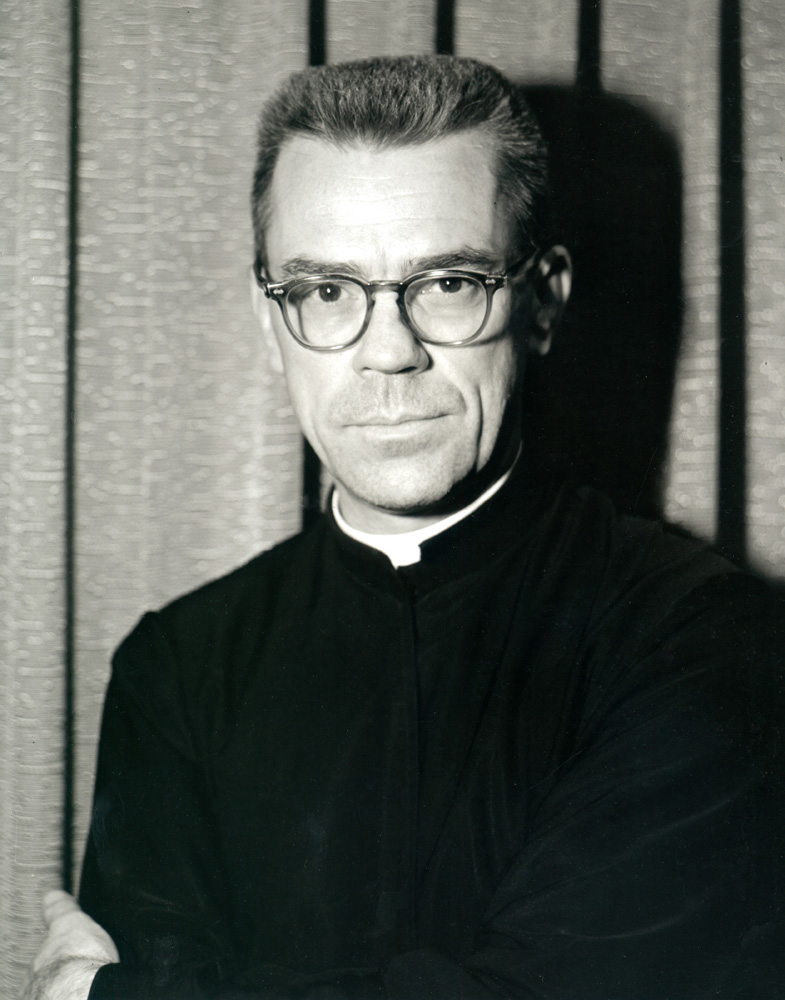

Father Luke,

Boleslaus T. Lukaszewski (1914-1970)

by John Waide, M.A.

This is the story of two Jesuit priests. One was born in the West Indies in 1840. The other was born in Milwaukee in 1914. The father of the Milwaukee Jesuit was born in Poland. Both future Jesuits entered the Society of Jesus at St. Stanislaus Seminary in Florissant, Missouri. The young man from the West Indies came to Florissant in August, 1863, while the other arrived at St. Stanislaus in 1932, a few years before World War II began. Although both priests taught at Saint Louis University, our 19th century Jesuit was a scientist, while the other taught philosophy. Although Saint Louis University was home base

for both men, the Jesuit scientist served as a missionary in Belize, traveled extensively, and knew and corresponded with scientists from all over the world, the philosophy teacher was more comfortable attending sporting events at Saint Louis University and being around the students.

Yet despite these numerous differences, these two men shared a common passion—photography. And it was a passion at which they both excelled. Between these two Jesuits, they took thousands of pictures of people, buildings, and numerous activities at Saint Louis University in both the 19th and 20th centuries. This is the story of Father Charles Marie Charroppin, the “quaint genius” of the Missouri Province, and Father Boleslaus Thomas Lukaszewski, Father Luke.

Our first story begins on the island of Guadeloupe in the West Indies on August 15, 1840. On that day, Charles Marie Charroppin was born. His family left Guadeloupe for St. Louis in 1848, and young Charles began attending the Academy at Saint Louis University in 1853 and then the collegiate course until 1857.

Charroppin entered the Society of Jesus in 1863 at the St. Stanislaus Seminary in Florissant, Missouri. After finishing his studies at Florissant, Charroppin spent four years serving at a Jesuit boy’s school in Cincinnati and then at St. Ignatius College, Chicago as prefect, director of the boy’s sodality, and French language instructor. Finally, he completed two years of theology courses in Woodstock, Maryland, before returning to St. Louis.

He was ordained on December 19, 1875, at St. John the Apostle Church in St. Louis. Following his ordination, Father Charroppin taught mathematics, chemistry and astronomy at Saint Louis University from 1876 to 1890. For three years, between 1891 and 1893, Father Charroppin served as an assistant pastor at St. Charles Borromeo Church in St. Charles, Missouri. In 1894, Charroppin was sent to Corozal, British Honduras (now Belize) where he spent four years as a missionary. He returned to the United States in 1898, and he spent the next twelve years teaching, taking photographs, lecturing on astronomical and other scientific topics, and speaking about his work in Central America, among other activities.

Father Charroppin returned to St. Charles Borromeo Church in 1910 where he served as associate pastor and as chaplain of the Religious Sisters of the Sacred Heart Convent in St. Charles. Father Charles M. Charroppin died in St. Charles on October 17, 1915, at the age of seventy-five.

To call Father Charles Charroppin an authentic Renaissance man is certainly true. To call him an eccentric and an unusual man is an understatement! In addition to his long academic teaching career at Saint Louis University, Charroppin was, among other things, a parish priest, a missionary, an accomplished photographer, an astrophotographer, a solar eclipse expert, an outstanding chess player, and an artist.

As was mentioned earlier, Charles Charroppin was born in 1840. Ironically, the year before his birth, a French artist by the name of Louis Daguerre had invented the first publicly available photographic process known as the daguerreotype. And Charroppin certainly made use of the photographic process. From the day he entered the Jesuits at St. Stanislaus Seminary in Florissant in 1863, Father Charroppin had a camera out taking pictures. At Florissant, he took photographs of his fellow Jesuits at work pitching hay, beekeeping, and repairing shoes. He even took pictures of them seated in the barber's chair.

While at Saint Louis University’s downtown campus, Charroppin took pictures of the St. Louis riverfront, buildings, bridges, towers, and parks. His photographs provide some of the earliest visual documentation of the City’s history. Father Charroppin photographed some of Saint Louis University’s earliest buildings. He took special care to document the University’s 1888 move from its downtown Ninth and Washington campus to its current location at Grand and Lindell.

Camera clubs were rather popular in the United States during the 1890s. The St. Louis Camera Club's minutes show that Father Charroppin served as one of the club’s officers and also mention that he had a darkroom at Saint Louis University. Father Charroppin's self-portraits reveal a rather quirky sense of humor. One of his self-portraits show him in his black cassock with a knowing gleam in his eye and a rosary at his side as he mixes powder with a mortar and pestle. Another rather dramatic photograph, which he called Meditation on Death,

shows him as a white-haired, bearded old monk in a two-tiered cape standing before a crucifix, skull, burning candle, and a picture of the Mary, the Sorrowful Mother. Another photograph shows Father Charroppin surrounded by an assemblage of woodland creatures.

In addition to his ordinary

photographic work, Father Charroppin became internationally known for his astrophotographic work. During his lifetime, Charroppin corresponded with many of the leading astronomers of this day and was frequently cited for his astrophotography and scientific work. Between 1889 and 1910, Father Charroppin traveled across the United States on the trail of various celestial phenomena like, particularly solar eclipses. He would be hailed by a newspaper of the time as St. Louis’ offering to the world of science.

Having gained a reputation as a gifted scientist and photographer, Father Charroppin frequently corresponded with astronomers at Harvard University, the University of Chicago, the University of California, Berkeley, and the Vatican Observatory. His friends included Max Wolf, the German professor who observed the return of Halley’s Comet to the solar system in 1910, and Percival Lowell, who founded the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff and who began the investigation that ultimately led to the discovery of the dwarf planet, Pluto. Newspapers across the country reported on his visits, views on the possibility of life on Mars and his pick for who would discover the North Pole.

Probably the most fascinating story about Father Charroppin and his astrophotography occurred at the time of a total eclipse of the sun on January 1, 1889. Charroppin was gathered with other astronomers and scientific colleagues to witness, and photograph, the total eclipse. Charroppin referred to such gatherings as eclipse parties.

Father Charroppin was gathered in California’s Sacramento Valley with colleagues from numerous observatories around the country. They were setting up their telescopes and camera equipment to photograph the upcoming celestial marvel. Unfortunately for Father Charroppin and his colleagues the weather that day was rather bleak with a layer of clouds blocking out any view of the sun. The forecast for the remainder of the day was not promising either.

Father Charroppin, however, was not deterred. According to several contemporary newspaper accounts, Charroppin gathered several groups of local school children who were there to observe the eclipse. He asked the children to help him pray for the clouds to clear. In an article published in a later issue of the Las Vegas Optic newspaper, Father Charroppin said: I thought of making an appeal to God for just two minutes’ clear sky at the moment of the total eclipse, which would occur at 12:15.

He told his disappointed scientist friends that We will have clear sky at the moment of totality – I will pray to the Blessed Virgin to intercede for us.

Charroppin told his friends that if his prayer failed, he would walk all the way to Sacramento, but if he was successful, all gathered would get on their knees and pray the Hail Mary

with their Jesuit colleague.

According to an account of Father Charroppin’s remarks shortly after the eclipse, Clouds on clouds swept over the sun, the darkness now became apparent; nature assumed an unearthly appearance; a greenish awe-inspiring light shone on the tips of the neighboring mountains…. Suddenly the clouds opened, the sun and moon appeared in a clear blue sky. A shout of joy and admiration burst forth from every pair of lungs. The last lingering ray of the sun disappeared; the corona burst forth in all its glory and majesty; four planets and many stars shone brightly. A perfect silence followed, disturbed only by our astronomical clock beating the half seconds.

Whether the scientists knelt and prayed the Hail Mary

was not recorded!

Over the years, Father Charroppin kept numerous notebooks. Some of these books were filled with illustrations of odd-looking creatures he drew which often combined human and animal forms. One person commented that these books were like medieval bestiaries.

Another of his notebooks contained more than two-hundred illustrations of chess moves as he was an avid chess player.

Stories about Father Charroppin from individuals who knew him clearly show his off beat

personality. One of his Jesuit colleagues, Father Ben Fulkerson, knew Father Charroppin from when Father Charroppin would come to the Fulkerson home for dinner. In one such story, Fulkerson told about a Catholic nun watching intently as Father Charropin bent over praying. After observing him for several minutes the nun asked Charroppin whether he was all right. Father Charroppin replied that yes, he was fine, but that he had discovered that his cigar box-and he loved smoking cigars-was empty. The sister looked puzzled, and then Charroppin said that he was waiting for heavenly replenishment.

Another person remarked that What people remember best about the bearded, portly priest was his thick, Caribbean accent, his telescope and his seemingly far-fetched talk bout the future. He would amaze our family with information about the heavens and with predictions of such things as the coming of air travel.

The world certainly lost a unique character when Father Charles Charroppin left us a little more than a century ago.

Now to the story of our second Jesuit photographer, Boleslaus Thomas Lukaszewski, or simply Father Luke.

He was born on February 7, 1914, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, to Anthony J. and Agnes Lukaszewski. His father was born in Poland while his mother was an American from Michigan. “Luke” had two brothers, Bernard J. and Anthony C. Lukaszewski, and four sisters, Helen, Lucy, Rose, and Martha. From 1921 to 1928, Luke

attended St. Vincent's Elementary School in Milwaukee, and from 1928 to 1932 he attended Marquette High School, also in Milwaukee. In 1932 he entered the Society of Jesus at St. Stanislaus Novitiate in Florissant, Missouri.

Luke

studied philosophy at Saint Louis University where he received his bachelor's degree in 1938 and his master's in 1940. From 1940 to 1942, Luke

taught English, Latin, French, and Theology at Creighton Preparatory School in Omaha, Nebraska. From 1942 to 1946 he studied theology at St. Mary's College in Kansas, receiving the Licentiate in Sacred Theology. He was ordained a Catholic priest in 1945. Following his Jesuit tertianship at Pomfret, Connecticut, he joined the philosophy faculty at Saint Louis University, where he served as Associate Professor of Philosophy for the next 23 years.

Although Father Luke

remained a lively and energetic philosophy professor his entire career, it was through his work as a photographer and not as a teacher that he left his mark on Saint Louis University. Even as he was completing his Jesuit training, Luke

won several prizes in local contests sponsored by the St. Louis papers for his photography. One of his prize-winning pictures, which he called Cleric,

featured his Jesuit classmate, Father John Walsh, who would also become a popular teacher at Saint Louis University.

Almost immediately after being assigned to the faculty at the University, Father Luke opened a photographic darkroom in the first floor of De Smet Hall. Early on, he became the premier cameraman for the University’s Athletic Department. He took both still photographs and motion picture films of virtually every home football, basketball, and baseball game. During the 1950s, the men’s basketball team featured several great players, Bob Ferry, Ray Sonnenberg, Jim Daley, Dick Boushka, and Bill and Bevo

Nordman. Father Luke became friends with each of these young men.

And when men’s soccer became an inter-collegiate sport in 1959, he took pictures and movies of the soccer games. He was able to travel with the soccer team for most of their away

games, including the NCAA tournament games. Many of his pictures and soccer films were included in a PBS/Nine Network documentary film and book called A Time for Champions: A St. Louis Soccer Dynasty. The film and book appeared in 2010 as part of the celebration of the 50th anniversary of Saint Louis University men’s soccer. The Billiken’s won ten NCAA Championships during the first fifteen years the NCAA sponsored a tournament, between 1959 and 1974!

Among the other close friends Father Luke had in the University’s Athletic Department were Bob Guelker, the University’s first soccer coach, Bob Stewart, the athletic director who brought soccer to the University, and athletic trainers Walter Eberhardt and Bob Bauman. Athletic Director Stewart suggested that Father Luke make a film of Baseball Cardinal great Stan Musial's final game at Busch Stadium (Sportsmen's Park) on North Grand. The film was Saint Louis University's gift to Stan, who was a generous benefactor of the sports program.

Other University departments called on him for posed photos as well as photos of their ordinary activities, and Father Luke always obliged. Many of his photographs were used by The University News (the student newspaper), the alumni magazine, and The Archive student yearbook. For the University’s sesquicentennial celebration in 1968, dozens of Father Luke’s photos were included in the pictorial history of this 150th anniversary. One of his best photos was taken in the morning when he was on the walkway between Du Bourg and De Smet Halls. It had snowed overnight, and Father Luke saw a beautiful snow scene in the Quadrangle with only a park bench and, as yet no footprints in the snow. The photo he took of this scene won first prize in the annual photo contest sponsored by the Kodak Company.

For more than twenty-years, between 1947 and 1970, Father Luke seemed to be everywhere on campus taking pictures of everyone and everything. On one occasion, while attempting to take an aerial shot of the Saint Louis University campus, he nearly fell out of the airplane! People seemed to have a smile when they saw Father Luke with his camera. He enjoyed being around the students and taking their pictures. As the students grew older, graduated, and became alumni, they would ask Father Luke to take pictures of their children whenever they would return to campus and visit with him. The students and their families would cherish Father Luke’s pictures for years.

Father Boleslaus Lukaszewski died suddenly in the Jesuit Residence at Saint Louis University on Palm Sunday afternoon, March 22, 1970, while watching television in his room. A visitor had left him at approximately 2:00, and he was found slumped in his chair at about 4:00 P.M., apparently the victim of a heart attack.

Fortunately for the University, Father John Francis Bannon, the pre-eminent historian and long-time chair of the Department of History, retrieved the more than 1,000 rolls of photographic negatives from Father Luke’s room. Although many of Father Luke’s pictures were used in various University publications, there were thousands more that were never published. Eventually these rolls of negatives found their way to the newly established University Archives in Pius XII Memorial Library in 1989. As Father Luke kept little notebooks containing information on the dates and subjects of each roll of pictures that he took. Thus, the Archives was able to easily describe each group of pictures. Over time, either photographic prints or digital scans of the more than 30,000 photographs Father Luke took of life at Saint Louis University were made. These images document the transformation of Saint Louis University from a relatively modest and unknown Midwestern college into a prestigious international university!