St. Louis Cultural History Project—Summer 2022

In Search of Stanley Kowalski

by Stephen A. Werner, Ph.D.

For theater and movie buffs of a certain age, the character of Stanley Kowalski remains iconic, either as seen in a theater performance of Tennessee Williams’ classic play A Streetcar Named Desire, or even more so in the legendary performance by Marlin Brando in the 1951 movie. And if one yells out “Stella!” the reference is instantly recognized. For several decades, the character of Stanley Kowalski was as well known as Hamilton is today.

I saw A Streetcar Named Desire in a small local production at the Kirkwood Theatre near St. Louis in the late 1970s. I did not get it! In fact, it was pretty disturbing. The play was chock-full of characters who were messed-up people. This was not the way people were supposed to be! But a decade later, after a number of life’s jolts, and learning more about the human condition, I began to understand the writing of Tennessee Williams. He told stories of messed-up people, of people who could not play the roles expected of them, of people damaged by the experience of life. His characters are at times uncomfortable to watch, but that was what he wanted to show us.

I cannot recall knowing of the death of Tennessee Williams in 1983. He died at age 71 in New York at the Hotel Elysée, choking to death on a plastic bottle cap. Years later, I heard the story that he often used his teeth to remove medicine bottle tops, and on this particular occasion, due to liquor or drugs, the top wound up in his throat. It turns out it was actually a much smaller top, the kind on a bottle of eyedrops. He had filled it with barbiturates to toss down his throat, and obviously, his plan went awry, as the cap went down with them.

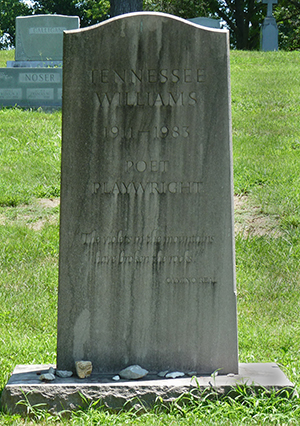

His body was brought to St. Louis where I lived. I wish I had been more aware at the time, for I could have gone to see him laid out at Lupton’s Chapel on Delmar near Midland in University City, or gone to the funeral at the New Cathedral, with Fr. Jerome Wilkerson, “the society priest,” preaching at the mass. (At that time the “New Cathedral,” it would later be upgraded to “Cathedral Basilica of Saint Louis.”) Per his brother Dakin’s decision, Williams was buried in the family plot at the Catholic Calvary Cemetery in North St. Louis, despite Tennessee’s request for a sea burial: “I wish to be sewn up in a canvas sack and dropped overboard, . . .”

But my friend Kit Kinsella, who taught me everything I knew about the St. Louis streetcar system, had long before taken me to the Central West End in St. Louis to find both the house where the poet T.S. Eliot had lived, at 4446 Westminster Place, and the apartment, two blocks west, of the Williams’ family at 4633 Westminster Place that became the inspiration for the setting of the play The Glass Menagerie.

When I created a one-credit seminar called “Tombstone” at the college where I taught I started giving regular tours of Calvary Cemetery in North St. Louis which always included a stop at Tennessee Williams’ grave, usually after the stop at Dred Scott’s grave. The plot for the Williams’ family used to be a six-foot tall light pink stone marker across the cemetery drive from a clump of river birch trees that always helped me find the spot. But the marker has weathered and beautiful birch trees have been cut down.

Sometime in the early 2000s I attended a performance of Suddenly, Last Summer at the Stray Dog Theatre in South St. Louis. There, to my surprise, amidst the small cluster of minglers in the lobby stood Dakin Williams, Tennessee’s brother. He was talking and I listened. He described how their father would call Tom (Tennessee’s nickname) a “nance.” I guess the goal was to shame Tom into becoming more manly. Dakin also described driving his mother, Edwina, the seventy miles down to the Missouri State Hospital No. 4 (for the insane) in the town of Farmington. They went to see her daughter and his sister Rose, who had been lobotomized in 1942. Rose would scream at the them for the entire visit.

I asked Dakin where he lived, and he said the retirement home at the Our Lady of the Snows Shrine in Belleville, Illinois, some twenty miles from St. Louis. As he left I made a mental note to go visit him. He seemed eager to talk and this would be a unique opportunity. And although I often follow up on such intentions, by the time I finally drove those twenty miles out to Our Lady of the Snows, he had been dead for several years. I could kick myself. Although Edith Piaf sang “Non, je ne regrette rien,” meaning “No, I Regret Nothing,” as for me, I regret plenty. And often for what I think are good reasons. In this case I had missed my unique opportunity to talk further with Dakin.

Then one day by chance, I saw a local newscaster on TV standing on Washington Avenue in downtown St. Louis, talking about Tennessee Williams working at the old International Shoe Building behind him (now the City Museum), and that Williams had met a Stanley Kowalski while working there.

There was an actual Stanley Kowalski? It was not simply a memorable character name, but an actual person! And so, I decided to track down Stanley Kowalski: the actual person! I found myself “In Search of Stanley Kowalski.”

My first step was to find his grave, which should have been easy. If he was Polish—unless Jewish—he would be in a Catholic cemetery. Stanley is a common Polish Catholic name in honor of the St. Stanislaus. (There are actually two St. Stanislaus’s and one St. Stanislaw in the Catholic history of Poland.) And I would later learn that Stanley Kowalski was a very popular name. One online search site lists some 350 Stanley Kowalski’s buried in the United States!

I searched the Archdiocese of St. Louis, Catholic Cemeteries, “Burial Search.” Unfortunately, I only found an infant with that name. Discouraged, and uncertain where to look next, and also distracted by my work teaching as an adjunct at four different universities I dropped the pursuit. Years later I would learn all about Ancestry.com.

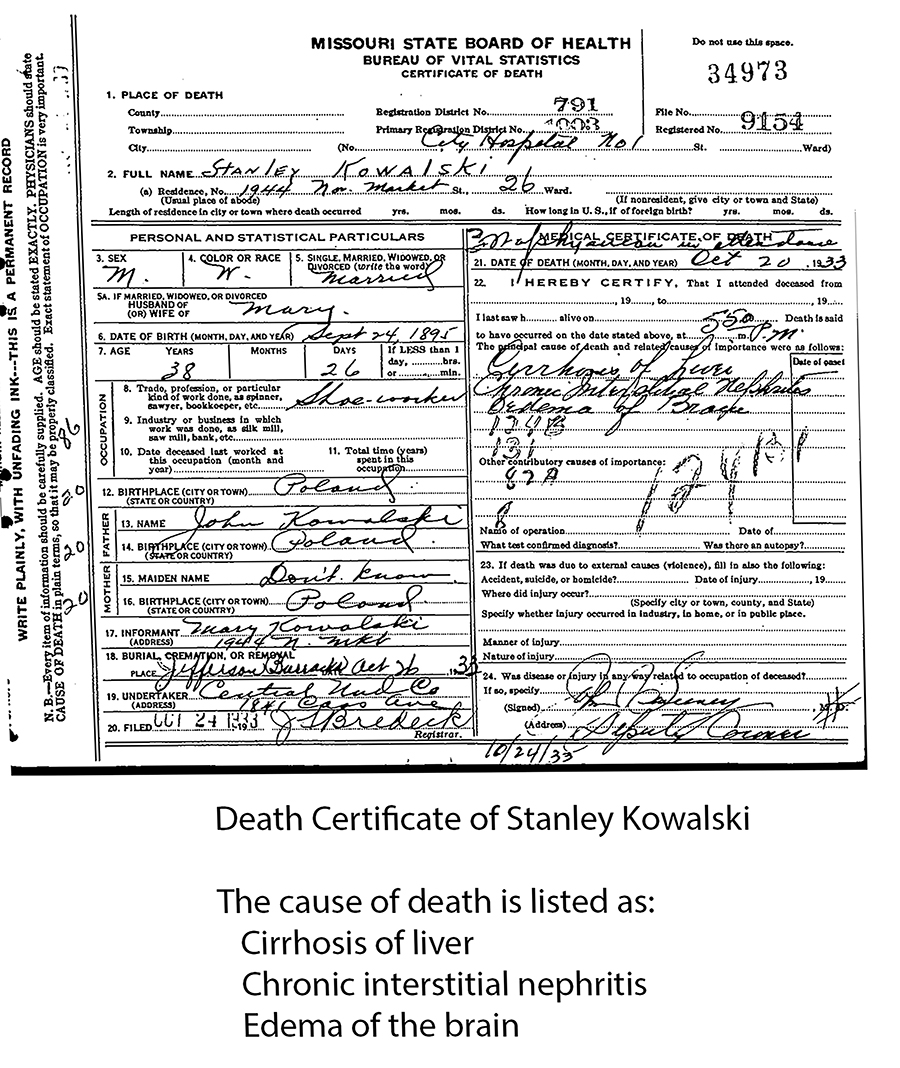

Then one day there was some issue with my Personal Property Tax and I had to go to the St. Louis City Hall building. And there on my way out of the tax office in City Hall I saw the sign on a door for Death Records. Did they have a record of a Stanley Kowalski? The woman did a quick search and moments later printed out the death certificate for Stanley Kowalski. [See below.] He did exist! And he was a shoe-worker who died in 1933! But he was buried not in a Catholic cemetery, but in Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery. He was a veteran. And I had the cause of his death, “Cirrhosis of the Liver.” Well, that would seem to fit the character Stanley Kowalski in the play and movie.

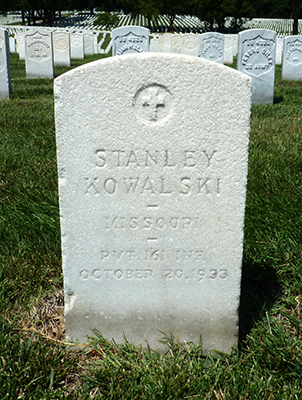

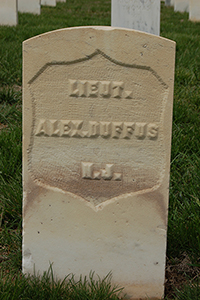

Next came a trip to what is known locally as “JB,” referring to either Jefferson Barracks Cemetery or the park next to it. And so at Section 38 4028-A, I found the grave of Stanley Kowalski. (Not far away was the grave of a Lieutenant Duffus. I did not know that was an actual name.) Kowalski had been in the 161 Infantry Division. Was he in World War I?

I next looked to see if the biographies of Tennessee Williams said anything about a real Stanley Kowalski.

One book by Donald Spoto stated:

At International Shoe, there was a dark, burly, amiable worker assigned to a job near Tom. He was everything the young poet was not—at ease in crowds and with strangers, sure of his strengths and confident of his ability to charm the ladies. He became Tom’s closest companion at the warehouse, and with him Tom apparently felt accepted, even protected from some of the harshness that otherwise surrounded his life. Soon, however, the man married, and about 10 years later he died. His name was Stanley Kowalski, and his family survived in Saint Louis for many years after. It is perhaps hard to know how much of his character and personality are represented by the character with that name in A Streetcar Named Desire, but the attraction to him by Blanche DuBois is certainly something that the playwright himself first knew. There is no evidence of a realized homosexual affair between Williams and Kowalski, but according to Dakin it was clear that Tom had a powerful erotic and romantic attachment to Kowalski; Kowalski’s name was often mentioned by Tom, and to see them together was to see a love-struck hero-worshipper and the idol of his dreams. .1

So now I had the story and all I had to do was to research this Stanley Kowalski to match these details. But what I soon discovered in the Genealogy Room in the St. Louis Public Library was that nothing matched this account.

I knew Stanley Kowalski was a shoe-worker from his death certificate, but I had nothing more to link him specifically to International Shoe. And Stanley died on October 20, 1933. When was Williams there? In his Memoirs he stated:

When I came home, Dad announced that he could no longer afford to keep me in college and that he was getting me a job in a branch of the International Shoe Company. The job was to last for three years, from 1931 to 1934. I received the wage of sixty-five dollars a month—it was the depression.2

The branch would be Continental Shoemakers. Other sources put Williams there from 1932-1935. Did Williams meet Kowalski there? Their years overlap. However, as a shoe-worker, Kowalski would have assumedly worked in the factory. But Williams worked in the sample rooms and as a clerk.

I got the job because Dad had procured for the top boss his position at the Continental Shoemaker’s branch. (This was still before the poker game and the decline and fall of “Big Daddy.”) Of course the bosses were anxious to find an excuse to get me out. They put me to the most tedious and arduous jobs. I had to dust off hundreds of shoes in the sample rooms every morning; then I had to spend several hours typing out factory orders. 3

But there are other problems connecting Williams to Kowalski. The biggest being that from October 12, 1931, until October 31, 1932, Stanley Kowalski was at the home for disabled veterans in Danville, Illinois, being treated for mild bronchitis, dental disease, and mild abrasions on the forehead. And although the years overlap, when Kowalski died in October of 1933, he was aged 38, and what shape would he have been in to soon die of cirrhosis of the liver? Did Kowalski even work for the last year of his life? So, who knows if the two met or had any interactions? Did the real Kowalski influence or inspire the character? Or did Williams just decide to use the name? Apparently, other names and nationalities were considered by Williams before deciding on the Polish Stanley Kowalski.4 Did Williams know that Kowalski had died? By using the name of a dead person, Williams could avoid the problem of a living person taking umbrage. But the idea that Williams had an attachment to Kowalski, as described in Spoto’s book based on the account of Dakin seems implausible.

Lyle Leverich, in his book TOM: The Unknown Tennessee Williams, states:

Tom had suffered the recent loss of the protective friendship of Stanley Kowalski, who married and left the shoe company. Like Harold Mitchell, he would be immortalized in A Streetcar Named Desire, but whether the Stanley Kowalski Tom knew bore any resemblance to his stage counterpart can only be conjectured. Evidently, there was some physical likeness, and it appears the two friends had a relationship of idol to hero-worshiper. Kowalski died about ten years later, and his family remained in St. Louis for some considerable time afterward, but little else is known about him.5

This account appears to be based on Spoto’s book which was based on Dakin’s recollections.

Was there another Stanley Kowalski? No evidence can be found that another Stanley lived in St. Louis at the time. Was Dakin totally wrong? Or perhaps there was someone else at the Continental Shoemakers that Williams admired, and Dakin got the name wrong.

And what about Stella Kowalski? Well the actual Stanley’s wife was Mary. The St. Louis Directory, the precursor of the phone book, in the 1920s and 1930s lists several women named Stella Kowalski. There is no way to know if the real Stanley knew any of them or if Williams met them. The 1930 census does show a Stanley Kowalski in Chicago married to a Stella, with children Chester and Eleanor.

The Known Details on the real Stanley Kowalski

Here is what I have tracked down about the real Stanley Kowalski.

He was born on November 2, 1893, in the town of Sępólno Krajeńskie, Poland, Russia.6 (His death certificate lists his birth as September 24, 1895. The death certificate also lists his father’s name as John.) He immigrated to the United States in 1913.7 He was part of a large wave of Polish immigrants. A 1932 medical record lists his married sister as Kate Cherry living in St. Louis.

Stanley registered for the military draft on June 5, 1917, in St. Louis. Woodrow Wilson had declared war on April 2, 1917. Stanley’s registration card describes him as being of medium height and build, with light brown eyes and black hair. A 1932 medical record would give his height as 5’ 5”.

On June 20, 1918, he married Mrs. Mary G. Lamkie; he was 25 and she was 36. The widowed Mary had three children who would have been about 18, 16, and 12. On June 27, Stanley was inducted into the Army. So many mysteries lie in these details! Why did he marry a woman ten years his senior with three children, a week before his induction into the army? His marriage certificate lists his address as 1606 Knapp St. in North St. Louis. This building, though boarded up, is one of two of his residences still standing.

Stanley Kowalski was sent to Camp Pike, Arkansas. Then he was assigned to Company C of the 161st Infantry. He was sent overseas to France from August 24, 1918, until July 8, 1919. In France, the 161st did not fight in combat, rather its soldiers were used as replacements in other units. He was discharged on September 10, 1919, from Camp Taylor in Kentucky. (In The Great Gatsby Jay Gatsby had been stationed at Camp Taylor.) Stanley’s record lists no engagements, nor any wounds or injuries. Nothing is known about his war experience.8

After the war, he returned to St. Louis. His name first appears in the St. Louis Directory in 1920 at 1616/2A N. 18th in North St. Louis. At the time, this ethnically diverse area included lots of Poles. His address would change to 1540A N. 16th in 1921, 2213A Carr in 1922, 1605A N. 17th in 1927-1929, the 912 N. 18th in 1930. None of the buildings are standing today. In some places the blocks have been rebuilt; other blocks are empty of buildings. Mary is only listed as his wife in 1930, so what was his relationship to Mary during these years?

As mentioned above, from October 12, 1931, until October 31, 1932, Stanley Kowalski lived at the home for disabled veterans in Danville, Illinois. In the 1932 Directory, he is listed without Mary at 3552 S. Broadway. This building is still standing.9 Also as mentioned above. Stanley died on October 20, 1933. He suffered from cirrhosis of the liver, chronic interstitial nephritis, and edema of the brain. Very likely he had been a serious alcoholic, but other than his death certificate no other evidence exists to prove this. Mary is listed on the death certificate as his wife.

The Life of Stanley’s Wife Mary

Mary Kwiatkowski, born in 1882, married Frank Lamkiewicz (Lamkie), born in 1880. The year of the marriage is unknown. They had two sons: Robert William, born in 1900, and Frank Lamkie, born in 1902. Mary’s husband Frank died sometime in 1905. She gave birth to a daughter, Gertrude, on November 17, 1905. In the 1910 census, Mary was living with her three children in the home of her father Frank Kwiatkowski at 1432 N. 15th.

Robert first appeared in the newspapers in July 1911, when at the age of 11, he stole a neighbor’s aged horse hoping to sell it to help his destitute mother. His mother had been sick and not able to work, and her mother Mrs. Annie Flowers threatened to throw her out. (They lived at 1217 N. 9th.)

At age 19, Robert married Mary Jane “Jennie” McKeever born 1900. In the 1920 census Robert is in the St. Louis Municipal City Jail. In the 1930 census Robert is in St. Louis City Workhouse. In August 1938, he would again in appear in the newspapers. Labeled as a “huckster” he got into an argument with a man who refused to buy him a drink. Robert was stabbed. He survived but would die on October 1, 1947.

The life of Frank was a mess. He first showed up in local papers in a car accident in June 1923. In June 1925, he was arrested with others for robbing several poker players of their money and jewels. In 1926 he was arrested in a payroll holdup and wound up in the State Penitentiary in Tennessee. Soon after his release he was one of four men who in October 1931 robbed a Metropolitan Life Insurance Company office in St. Louis of $4,580. He pled guilty and was sentenced to five years in the state penitentiary in Jefferson City, Missouri, but died in prison of tuberculous on November 7, 1932.

Gertrude married Edward Gadell in 1921 or 1922. He had served in World War I. In the 1930 census Mary Lamkie, listed as divorced, would be living with them.

Mary would experience much tragedy in those years. Her brother Thomas died in 1930. Her son Frank died in 1932. Her divorced husband died in October, 1933. And her daughter, Gertrude Gadell, died in January 27, 1935.

So far, I have not found any trace of Mary after the 1935 obituary for her daughter.

A Mary Lamkie would die on January 21, 1962, and be buried in the indigent section of Calvary Cemetery. Her death certificate gives her birth as January 17, 1893. If this date is correct she could not have been the Mary Lamkie who married Stanley Kowalski in 1917 at the age of 36. And it is unlikely she is the Mary who married Robert Lamkie.

Mary’s son-in-law, the widower Edward Gadell would serve in World War II and return to St. Louis to work as a chauffer. In 1951, he married Matilda Bolckmann. He died on January 31, 1963, from cirrhosis of the liver and alcoholism.

Another Polish Fellow

In his Memoirs Williams mentions a friend he met at Continental Shoe. “Still, I learned a lot there about the comradeship between co-workers at minimal salary, and I made some very good friends, especially a Polish fellow named Eddie, who sort of took me under his wings, and girl named Doretta, with whom Eddie was infatuated.”10 This was Eddie (Edward) Zawadzki. The 1932 and 1933 St. Louis Directory lists an Edward Zawadzki as a clerk at International Shoe, living at 1521 N. 14th St. with his mother Adele and brothers August, Charles, Frank, and Gustav.

As quoted above, the book by Spoto describes Stanley Kowalski: “At International Shoe, there was a dark, burly, amiable worker assigned to a job near Tom. . . . Soon, however, the man married, and about ten years later he died. His name was Stanley Kowalski, and his family survived in Saint Louis for many years after.”

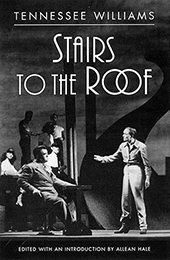

Is it possible that this person was Eddie Zawadzki and not Stanley Kowalski? Eddie seems to fit this description, although ten years later Eddie went into the army for World War II. He died in 1975. Eddie’s October 1940 draft registration card describes him: height—5’ 8”, weight—196 lbs., complexion—dark, hair—brown, and eyes—brown. So he met the “dark” description. At 196 lbs., would he have been “burly”? Also, the Zawadzki family survived, there was no Kowalski family to survive after his death. Williams would dedicate his play Stairs to the Roof to Eddie and Doretta.

This play . . .was written involuntarily as a katharsis of eighteen months that I once spent as a clerk in a large wholesale corporation in the Middle West. This eighteen months’ interlude, my season in hell, came at a time when I was just out of high school [Williams had finished three years of college.] and the world appeared to be a place of infinite and exciting possibilities. I discovered how badly mistaken it is possible for a young man to be.

I escaped to college.

I left the others behind me—Eddie, Doretta, Nora, Jimmie, Dell—and I never went back to see if they were still there. I believe they are.

THIS PLAY IS DEDICATED TO THEM.

I dedicate it to them and to all of the other little wage-earners of the world not only with affection, but with profound respect and earnest prayer.11

Edward Peter Zawadzki was born on October 13, 1910. Eddie and Doretta Henrietta Oseland married and then Eddie served in World War II. He died on July 4, 1975. Doretta would live to the age of 96 and die on June 6, 2007. Perhaps Eddie and Doretta had a successful relationship and marriage and thus inspired no characters in the plays of Tennessee Williams.

And so, my “Search for Stanley Kowalski” has come to an end. What I mostly discovered was what apparently did not happen: that Tennessee Williams based his character of Stanley Kowalski on an actual person by that name with whom he had extensive contact.

As with a prayer ending with “Amen” I cannot resist the temptation to end this essay with a one-word exclamation: “Stella!”12

Now I move on to my next project: “In Search of Evelyn West,” the legendary St. Louis exotic dancer.

FOOTNOTES

- 1 Donald Spoto, The Kindness of Strangers: The Life of Tennessee Williams (Boston: Little Brown, c1985), 44.

- 2 Tennessee Williams, Memoirs (Garden City, N.Y. Doubleday, 1975), 36.

- 3 Ibid.

- 4 Joseph W. Zurawski, “Out of Focus: The Polish American Image in Film” Polish American Studies, Vol. 70, No. 1 (Spring 2013), 9, 11.

- 5 (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1993), 149.

- 6 This comes from his military registration card which spells the place name as “Sepolno, Kalisz.” However, this birth date is uncertain. The month “November” is followed by what could be a 2 or a question mark.

- 7 Per the 1930 census.

- 8 His military records are available at the Federal Records Center in St. Louis, but contain little information.

- 9 The building at 3550 is still in use. Possibly, 3552 originally shared the front entrance.

- 10 Memoirs, 36-37.

- 11 Tennessee Williams, Stairs to the Roof (New York, New Directions, 2000), xxi.

- 12 If the reader does not know why I had to add this ending the reader might not understand the whole reason for this essay.