EXTRA MATERIAL

Chapter Thirty

The Legacy of Daniel Lord, S.J., The Restless Flame

The Eulogy of Daniel Lord

His funeral took place on 19 January 1955. At College Church, where Lord had been ordained in 1923, Auxiliary Bishop Charles H. Helmsing delivered the eulogy.

We know that anyone who tries to present the teachings of the Church in a popular way must at times run the risk of perhaps giving a wrong impression. But again I say the safety valve is this guidance that the Church provides, decreeing that all writing be submitted to trained theologians.1

It is sad that of all the points to be made about Lord, the issue of control would need to be asserted. Most of the comments made by Daniel Lord’s censors were details for clarification. They never censored Lord on his theological views since they were so in-sync with church teaching. The great tragedy was that no one could fill Lord’s shoes.

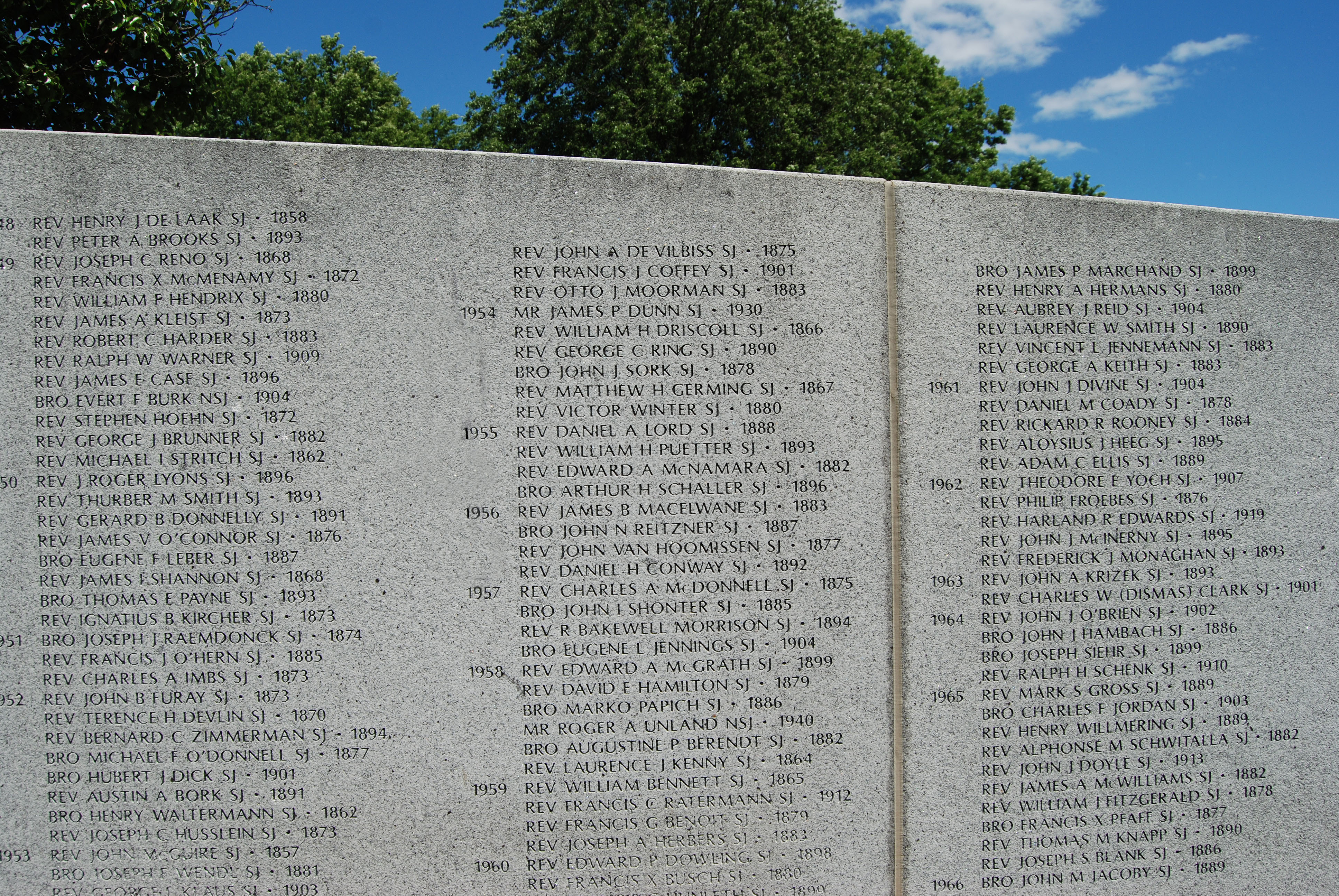

Daniel Lord second burial site in Calvary Cemetery.

Two Biographies

Joseph McGloin, S.J. wrote Backstage Minister: Father Dan Lord, S.J. (1958). Father Faherty thought the title was misleading: Lord was never in the background, he was always front and center. This book provides a quick introduction to Lord and a feel for the kind of person he was. The book includes several conversations between Lord and other people. Did other Jesuits relate these conversations or did McGloin create them?

Thomas F. Gavin, S.J. wrote Champion of Youth: A Dynamic Story of a Dynamic Man: Daniel Lord, S.J. (1977). John Cardinal Wright wrote an introduction that unfortunately sets the wrong tone for the book by claiming that Lord had failed in his vision to bring unity to Catholics. Lord never wrote about such a vision, he was too busy trying to the get the group in front of him excited about their faith.

In researching his book, Thomas Gavin found the letters Lord wrote during his retreat in the hospital in January 1954 and published these in 1969 as Letters To My Lord. They are surprisingly frank thoughts of a man’s religious faith. The book is not a timelessly profound reflection on the mystery of life in the face of death. Rather it is Daniel Lord expressing his day-to-day religious faith.

This book also contains a distracting preface by John Cardinal Wright that should be skipped. A review of the book states:

This is no mamby-pamby pietism but an outpouring of spirit so direct, so lyrical, and so poignant as to be rather frightening to those of us afraid of our own emotions, stingy with expressions of warmth or personal feeling.2

Assessments of Daniel Lord

Lord’s fellow Jesuit and friend Bakewell Morrison in his Introduction for Played by Ear wrote:

He dreamed, for example of beauty, though he did not often say the word. He rather wanted to create it than to talk about it. He tried, in pageantry especially, and in his rhythmed prose, to make his dream come articulate—his dream of celestial beauty.

With human voices, human gestures, human beings—and rhythm, and color, and sound—he attempted to impress the fact of beauty, the philosophy of beauty. He was hungry for the sight, the feel, the sound, the taste of it, the very smell of it. His hunger was for the beauty of God; and so, with all his resources, he tried to make that beauty recognizable and real to others, to all others; they, like himself, had to be hungry for beauty.3

Jesuit historian William Barnaby Faherty wrote on the importance of Lord:

He produced plays and pageants; he engaged in public debates; he lectured; he conducted a successful radio program; he advised movie producers on Catholic attitudes; he served as chief consultant for Vigilanti Cura, Pius XI’s encyclical on the movies; he counselled married couples; he wrote books. Throughout this vast activity, bits of his genius showed intermittently. Without question he could have produced a play, an operetta, a novel, a piece of non-fiction that would have endured. But the versatile apostle was concerned with the here-and-now religious needs of people. . . .

Father Lord taught an entire generation that religion should permeate life with true joy in the possession of God. He brought optimism into the heart of American Catholic living.

. . .

He was one of the most deeply revered priests of his generation.4

The Catholic historian Jay Dolan summarized the impact of Lord:

In keeping with the 20th-century emphasis on the apostolate of the young, the sodality movement experienced a renaissance in the 1920s and 1930s. The main force behind this was the Jesuit priest Daniel Lord. . . . He promoted the sodality and its appeal and its special brand of devotional Catholicism in a variety of ways: through a magazine, pamphlets, theater, summer schools of Catholic action, and national conventions.5

Lord received this recognition in 1970:

His popularity was enormous and incalculable, and he probably did as much as any other single individual to make Catholicism plausible and highly lovable to at least two generations of American young people.6

A 2005 article describes Daniel Lord:

. . . he represents a pioneering vision for the church’s ministry in a modern, media-saturated world. Lord championed a form of public Catholicism meant to compel youth to take their faith out into the world, not to leave it sequestered in churches and schools, “safe” from spreading. What appealed to a generation of Catholic youth and what should elicit our admiration today is Lord’s zeal to communicate with people using the most effective means available, whether the stage, the written word or the cinema. Lord’s works connected the faith with the experiences and interests of youth, employing modern technology and cultural themes without shortchanging the vitality of the church’s teachings.

Lord’s ability to engage and energize youth was unmatched in his time.7

Thomas Gavin noted:

Someone had made an estimate that he turned out an average of 20,000 words a month for over 35 years. That, of course, does not include the tens of thousands of letters which he wrote.8

This would amount to eight million published words.

What Happened to the Characters Created by Daniel Lord?

What happened to the fictional characters Lord had created: Father Hall, the Bradley Twins, Helen Webb and Fred Osborne, Joe College, Jane Soph, and Chick Pagan? They were all greatly affected by World War II.

Chick Pagan went to law school and became a well-known prosecuting attorney, always asking tough questions. During the war he was recruited by the OSS, which became the CIA. He worked in Europe during and after the war. What he did during those years is not known: his files have never been declassified.

He left the CIA, a disillusioned man, and started drinking too much. On night he stumbled into an A.A. meeting. He read all the Daniel Lord pamphlets recommended for alcoholics by Edward Dowling. He started going to church and reclaimed his given name: Charles Pagano. Then he read Thomas Merton’s Seven Storey Mountain and set off for Gethsemane, Kentucky and joined the Trappists. He left after five years and set up a small law firm, spending much of his time giving legal help to the poor. He joined VISTA in 1965. Never married, he died in 1993.

As for Joe College: during a touch football game he injured his knee badly enough to disqualify him from service. He earned a Ph.D. and became a well-respected university philosophy professor. He married and had three children. He died in 1977. Jane Soph married a Kowalski and raised a family. She died 1983.

Helen Webb continued writing. During the war she worked in a New York publishing firm and moved up quickly due to her ability and the many opportunities created by men being in the military. She started going to Catholic Catechism classes and became Catholic. At some point she fell in love with Aaron Bernstein, a cousin of the famous Leonard. Helen and Aaron married and had three children and in time she drifted away from her faith. They would eventually try the Unitarian Church for a few years. She died in 1986.

Ford Osborne continued to write for popular magazines and gained some attention in literary circles. During the war he enlisted in the Air Corps and became captain of a B-17. He flew numerous missions, but found them terrifying. He also became deeply troubled over the carpet bombing of cities. His plane was shot down in February 1945 over Dresden. It was presumbed he died.

Dick Bradley enlisted in the Navy and was sent to the South Pacific where he captained a Patrol Torpedo Boat: PT 108. He married after the war and became a high school history teacher.

Sue Bradley married in 1937. Her husband was drafted and wound up in Army Logistics. Sue took an office job in a defense plant where she caught tuberculosis. However an antibiotic to treat TB had just been developed so she only spent a few months in a sanatorium.

After the war, Dick and Sue both wound up in new parishes built in the new suburbs on what had once been farmland. Between the two families they had nine children including a Joan, a Mary and a Teresa. One boy got polio and would need braces and crutches the rest of his life. One of the boys became a Jesuit who later became a friend of the Berrigan brothers. Two of the girls became sisters: one joined the Daughters of Charity and the other the Sisters of Mercy. The Daughter of Charity left the order in 1965, got married and started a family. The other as a Sister of Mercy, got a Ph.D. in theology, taught at a university, and became a well-respected scholar until she had a debilitating stroke. She spent the last years of her life in a nursing home for sisters. Dick Bradley died in 1981 and Sue in 1984.

Father Hall lived at Lakeside for a few more years; but his gig was too good to last. His superior assigned him to teach and be an administrator at a Catholic college. Although he enjoyed teaching, his writing suffered because he was so busy. However, during summer breaks he did write a popular series about a priest who solved crimes: the Father Tom Playfair Mysteries. He died 1972.

NOTES

- 1 Copy of Eulogy in Jesuit Archives.

- 2 Victor Newton, Sign 49 (April 1970), 52.

- 3 Played by Ear, viii.

- 4 Faherty, Better the Dream, 358.

- 5 Dolan, American Catholic Experience, 386.

- 6 F. Clinton Triumph 5: (July 1970), 37.

- 7 Endres, “Dan Lord, Hollywood Priest,” 21.

- 8 Gavin, 175.

Copyright 2021 Stephen Werner