St. Louis Cultural History Project—Spring 2021

The Life, Social Thought and Work of

Joseph Caspar Husslein, S.J.

by Stephen A. Werner

(This article was previously published in Gerard S. Sloyan, ed., Religions of the Book, the Annual Volume of the College Theology Society 38 (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1992) © College Theology Society.)

1992 marked the fortieth anniversary of the death of Joseph Husslein, a largely forgotten but significant figure in American Catholicism. In the early 1900s he was a leader in Catholic social thought, in the 1930s and 1940s a leader in promoting Catholic literature.

Born in 1873, Husslein grew up in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.1 He was graduated from Marquette College (later Marquette University) and in 1891 he entered the Society of Jesus at St. Stanislaus Seminary near St. Louis, Missouri. For several years he taught at Saint Louis University and was ordained a priest in 1905. In 1911 Husslein joined the staff of the Jesuit weekly America in New York. During the next eighteen years he wrote eleven books and hundreds of articles in Catholic journals on the Christian response to social problems. He attempted to reach a wide Catholic audience with his writings.

The encyclical Rerum Novarum (1891) of Pope Leo XIII (1810-1903) provided the foundation for Husslein's social thought; but the experiences of American Catholics also influenced him. Due to immigration the Catholic population in America mushroomed. Many Catholics suffered under the industrialization of the late 1800s and early 1900s. Workers often labored in unhealthy and dangerous factories for very low pay. Fearing these desperate workers would join the burgeoning socialist movement, the Catholic Church became involved in social problems.2

Several controversies, however, prevented Catholics from developing an American answer to social problems: the controversy over the writings of Henry George; the controversy over Catholic recognition of the nationwide union, the Knights of Labor; and the controversy over Americanism--how far Catholicism should adjust to American culture. Thus Husslein looked to Rerum Novarum for answers.

Husslein was one of several pioneers who applied Catholic teachings to the American setting, among whom John A. Ryan (1869-1945) was the most important and best known. Other significant figures were Frederick p. Kenkel (1863-1952) of the Central Bureau of the Central Verein (an organization of German-American benevolent societies, located in St. Louis), William J. Kerby (1870-1936, a priest of the Archdiocese of Dubuque at the Catholic University of America and Trinity College), William J. Engelen, S.J. (1872-1937--at Saint Louis University), Peter E. Dietz (1878-1947, a labor activist priest who worked in Cincinnati, Ohio), and the Jesuit writers at America.

Husslein believed the Catholic Church had the answers to social problems. Rerum Novarum boldly made such a claim, For no practical solution of this question (i.e., the alleviation of the condition of the masses) will be found without the assistance of religion and the Church.

3 Husslein applied Leo XIII's ideas under four main themes: an explanation of history, a critique of capitalism, a rejection of socialism, and Husslein's alternative, Democratic Industry.

HUSSLEIN'S EXPLANATION OF HISTORY

Husslein answered the criticism often made by socialists that the Catholic Church neglected the poor and workers.4 Pulling together the threads of Leo XIII's views of history, Husslein argued that the Church alone had advanced the cause of workers. Husslein surveyed history, starting with the Old Testament, to show true religion as the protector of workers. From the early Christian centuries to the middle ages the Church worked to abolish slavery, to humanize serfdom, and to protect labor. According to Husslein, the medieval guilds represented the high point of the Church's effort. Tragically, during the Reformation the guilds were destroyed and the moral teachings of the Church rejected. This led to the disastrous consequences of the industrial revolution under laissez faire capitalism. Unfortunately, Husslein reshaped history around his polemical position, and in doing so, failed to treat history critically.

HUSSLEIN'S CRITIQUE OF CAPITALISM

Husslein vehemently attacked laissez faire capitalism:

We still have men in business for whom there is but one industrial principle, and that is the law of supply and demand; for whom labor is but a commodity upon the market to be purchased at the lowest price and worked to the utmost limits that so they may procure through it the highest profits; for whom, in fine, all considerations urged for the need of adequate family wages, such as may suffice to keep the mother engaged in the care of her children amid the decent comfort of a happy home, are pure sentimentalism which has no place in business, commerce, and finance. It is that class of men, devoid of practical Christianity or true religious principles--and let us hope their number is daily growing less!--which is the real menace of industry and civilization, far more than Socialism, Anarchism, or the whole Soviet regime of Bolshevism ever could possibly be. Such men, precisely, are the most responsible for all radical systems and labor revolutions that disturb the world.5

Husslein lamented the system of ethics that justified this:

Its law was summed up in the materialistic motto:Business is business,which means that the considerations of humanity and religion may have their proper time and place, but must not be allowed to interfere with the interests of personal gain. A man might grind and crush the poor, pay starvation wages to labor and exact starvation prices for his products, and yet stand justified by the principles of this system. He might even, if he chose, be crowned as a philanthropist and public benefactor, to satisfy his craving for publicity. Such a code of morality was impossible in the Middle Ages.6

Husslein attacked the injustice of capitalism. In a typical article entitled, The Message of Dynamite

on the bombing of the anti-union Times of Los Angeles in 1910 by radical unionists, Husslein condemned the bombing but then turned on business:

It is important however, that the crimes of capital be weighed in the same scales as the crimes of labor, and that the same Nemesis overtake them both. It is needless to enumerate the scores of industrial accidents, the poisoning, the crippling and premature death brought on by the neglect of capitalism providing the proper means of safety and sanitation where the need of them was sufficiently understood. Although such neglect was not always criminal, yet there are instances where the fatal results could have been worked out with almost mathematical certainty. Not infrequently the wasting diseases or sudden deaths due to manufacturing processes and conditions of labor could readily have been averted, but the remedy would have diminished to some extent the streams of dividends pouring into the overflowing reservoirs of wealth. Gold has proved more deadly to the human race than dynamite.7

In making his attacks on capitalism, Husslein fit the model of the Old Testament prophet who used the language of metaphor, hyperbole, and image to attack social injustice.

Husslein fought specific abuses such as child labor, unsafe factories, and unhealthy work conditions. Although he opposed what he considered radical elements in the feminist movement, Husslein called for equal pay for equal work for women and protection for women from dangerous occupations. Husslein also attacked sexual harassment in the work place.

HUSSLEIN'S REJECTION OF SOCIALISM

Husslein saw unrestrained capitalism as the source of socialism. Desperate workers suffering under the capitalist system turned to socialism. But Husslein rejected socialism, primarily because of its irreligion.8 He believed that only true religion could solve the problems of workers. In particular he attacked socialist claims of neutrality toward religion. He quoted the Chicago Platform of the 1908 National Conference of the Socialist Party of America: The Socialist Party is primarily an economic and political movement. It is not concerned with matters of religious belief.

9 Husslein called this statement a subterfuge, a tactical falsehood to attract members. Let us, then, make no mistake. True Christianity and true Socialism, as here described, are forever irreconcilable.

10

Husslein attacked and rejected revisionist or mitigated socialism which sought change through democratic and parliamentary means--promoting evolutionary socialism instead of radical, revolutionary socialism. Husslein cited Pius XI who stated, No one can be at the same time a sincere Catholic and a true socialist.

11

HUSSLEIN'S DEMOCRATIC INDUSTRY

Private property was the most developed argument in Leo XIII's Rerum Novarum. Yet the property argument proved difficult to apply. Apparently Leo XIII envisioned an agrarian or crafts economy and not a modern industrial economy when he called for a wider distribution of private property.12

Husslein attempted to salvage Leo XIII's insistence on private property as the solution to the social question by combining it with the pope's views on history. Thus Husslein applied the principles of the medieval guilds to modern worker cooperatives. Not a nai've romantic wanting to return to the middle ages, Husslein believed that guild principles such as the insistence on quality, worker control of enterprises, and regulations for fair prices were essential to bringing justice to modern economic systems. It is clear that the guilds cannot be reproduced today precisely as they existed in the middle ages. . . . What we can and must copy is their spirit and motivation.

13 Husslein called his application of guild principles to modern economies, Democratic Industry.

For Husslein, Democratic Industry involved five specific and concrete approaches: profit sharing, cooperative banks, cooperative stores, co-partnership, and co-production.14 Husslein envisioned a mixed economy: cooperative industries alongside capitalist industries.

In profit sharing, the workers' receipt of a share of profits presupposed living wages for workers. Husslein considered this a positive step, but an inadequate solution to the industrial problem, since workers had no share in management of the business.

In cooperative banks or credit unions, workers and poor people could obtain credit when refused by commercial banks and escape usurious interest rates. Husslein described cooperative stores where members owned shares of stock in stores where they purchased goods at low prices. Cooperative stores eliminated middlemen who raised prices without providing tangible service to consumers.

In co-partnership, the fourth approach, workers owned a substantial share in voting stock and a reasonable share in management. Unions would still be necessary.

Finally, Husslein proposed co-production (also called cooperative production and cooperative ownership), in which workers owned and managed the businesses in which they worked. He saw this approach as voluntaristic, not socialistic, and based on private, not public, ownership.

Husslein believed that these cooperatives would benefit and protect workers, give them control over their lives, and stop the economic injustices of modern society such as shoddy products, market hoarding, price fixing, price gouging, and inadequate wages. Furthermore, Husslein thought that cooperatives could reach these goals without government intervention.

Husslein, possibly the most prolific American Catholic social thinker, wrote some five hundred signed articles, countless unsigned articles, and eleven books on social issues. His first book published in 1911 was The Church and Social Problems. The Catholic's Work in the World, published in 1917, provided a handbook for organizing Catholics, probably modeled after socialist handbooks.15 It contained a chapter on religious conversion entitled, Win my Chum week.

An outstanding book was Husslein's Bible and Labor published in 1924.16 This book, unique in American Catholic thought until recent times, attempted to develop principles for social ethics from biblical--largely Old Testament--principles.

The bulk of Husslein's social writing ended with his book The Christian Social Manifesto which appears to be, for its time, the definitive American interpretation of Rerum Novarum and Pius XI's Quadragesimo Anno. Husslein based this book on his radio broadcasts of Catholic social teaching.

Husslein bridged the period between Leo XIII and Pius XI. In many points, by drawing out the implications of Leo XIII's thought Husslein anticipated Pius XI. Husslein received international recognition for his work.

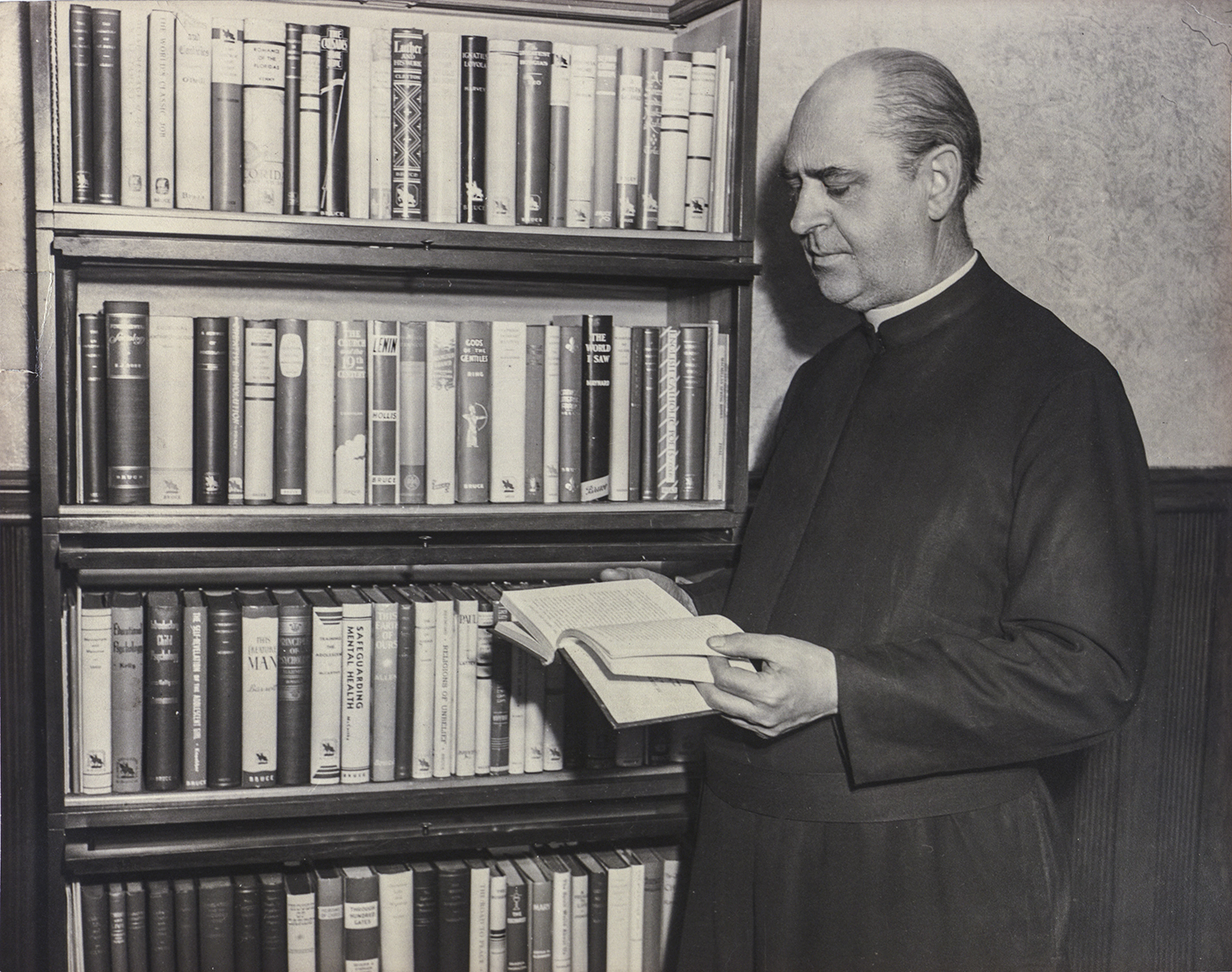

A UNIVERSITY IN PRINT

In the early 1930s Husslein returned to Saint Louis University and founded its School of Social Service to train social workers. During the Great Depression many Catholic universities established similar schools. Husslein sought an organization to promote and develop Catholic social science and to train professional social workers. Husslein directed the school until 1940.

Husslein also had in mind a more daring project. In 1931 he founded A University in Print,

a collection of books to promote Catholic scholarship, published by Bruce Publishing ofMilwaukee.17 In Husslein's time the shortage of American Catholic literature and scholarship was widely lamented. There was a deliberate effort to create and encourage an American Catholic literary revival and to promote Catholic intellectual efforts.18 Husslein desired to establish a university in print with books of biography, history, literature, education, the natural sciences, art, architecture, psychology, philosophy, scripture, and religion:

It was to be a university for the people, a university for the men and women with intellectual interests, whether within college walls or outside of them, offering to all the best scientific and cultural thought of Catholic thinkers, scientists and literary men. Each work was intended to be the result of original research while at the same time presenting larger and more familiar aspects of the subjects treated. It was to be popular, but without sacrificing scholarship.19

Husslein envisioned A University in Print

with a faculty of productive Catholic authors, their books as lectures, and the world as their student body. Although started in the Great Depression, the series grew rapidly. It included such authors as Hilaire Belloc and Fulton J. Sheen. Husslein's A University in Print

began with the first group of books the Science and Culture Series.

A year and a half later Husslein began the Science and Culture Texts

series and in May 1934 Husslein started a third series: the Religion and Culture Series.

Working without a secretary, Husslein edited over 212 books during a twenty-one year period. The series included Husslein's two-volume Social Wellsprings which provided English translations of the social encyclicals of Leo XIII and Pius XI. Also the series published several of Husslein's eight devotional books on such topics as the kingship of Christ, the biblical roots of Eucharist, and Therese of Lisieux.

All of Husslein's work flowed from his belief that the Church,had the answers to social problems. Husslein labored throughout his life to disseminate Catholic teaching and to prove the viability of this belief. In his social writing and his founding of the School of Social Service at Saint Louis University he applied and promoted Catholic social teaching. In his A University in Print

and devotional writing he promoted Catholic teaching and spirituality as the catalyst for social reform. Husslein's work represents a unique and important contribution to American Catholicism.

NOTES

- 1 Several short articles describe the life and work of Husslein: The New Catholic Encyclopedia, s.v.

Husslein, Joseph Caspar,

by E. J. Duff; Matthew Hoehn, ed., Catholic Authors: Contemporary Biographical Sketches: 1930-1947 (Newark, N.J.: St. Mary's, 1957), 344-45;Rev. Joseph A. [sic] Husslein,

The News-Letter--Missouri Province 17 (February 1953): 139-41; George G. Higgins,Joseph Caspar Husslein, S.J.: Pioneer Social Scholar,

Social Order 3 (February 1953): 51-53; Walter Romig, ed., The Book of Catholic Authors: (First Series) (Grosse Pointe, Mich.: Walter Romig, 1942), 131-38. Archival material exists at the Jesuit Archives at 4517 West Pine, St. Louis, Mo. The most detailed study is Stephen A. Werner,The Life, Social Thought, and Work of Joseph Caspar Husslein, S.J.

(Ph.D. diss., Saint Louis University, 1990). The only recent writing on Husslein has been Peter McDonough, Men Astutely Trained: A History of the Jesuits in the American Century (New York: Free Press, 1992). This book incorporates a previous article by McDonough that discusses Husslein:Metamorphoses ofthe Jesuits: Sexual Identity, Gender Roles, and Hierarchy in Catholicism,

Comparative Studies in Society and History 32 (April 1990): 325-56. However it is this writer's opinion that McDonough does not accurately interpret Husslein or his writings. - 2 For general works on American Catholic social thought in the early 1900s see Aaron I. Abell, American Catholicism and Social Action: A Search for Social Justice, 1865-1950 (New York: Doubleday, 1960); Charles E. Curran, American Catholic Social Ethics: Twentieth Century Approaches (Notre Dame, Ind.: Notre Dame, 1982); and James E. Roohan, American Catholics and the Social Question 1865-1900 (New York: Arno, 1976).

- 3 Leo XIII, Rerum Novarum, 13; found in Joseph Husslein, Social Wellsprings, Vol. 1 (Milwaukee: Bruce, 1949), p. 175.

- 4 Husslein developed his views on history in three books: Bible and Labor (New York: Macmillan, 1924); Democratic1ndustry (New York: p. J. Kenedy, 1919); Joseph Husslein and John C. Reville, What Luther Taught (London: R. & T. Washbourne, 1918).

- 5 Joseph Husslein, The Christian Social Manifesto (Milwaukee: Bruce, 1931), p. 44.

- 6 Husslein, The World Problem: Capital, Labor and the Church (New York: p. J. Kenedy, 1918), pp. 37-38.

- 7 Joseph Husslein,

The Message of Dynamite,

America 8 (8 February 1913): 414. - 8 Husslein's attack on socialism permeates his writings but is clearly stated in The Church and Social Problems (New York: America, 1912).

- 9 Husslein, Church and Social Problems, p. 25. See also pp. 25-31.

- 10 Husslein, Christian Social Manifesto, p. 85.

- 11 Pius XI, Quadragesimo Anno, 39; found in Husslein, Christian Social Manifesto, p. 314.

- 12 Charles Curran,

The Changing Anthropological Bases of Catholic Social Ethics,

The Thomist 45 (April 1981): 307-308. - 13 Husslein, Social Wellsprings, 1:190.

- 14 Joseph Husslein, The World Problem: Capital, Labor, and the Church, (New York: p. J. Kenedy, 1918), pp. 203-31.

- 15 Joseph Husslein, The Catholic's Work in the World (New York: Benziger, 1917).

- 16 Joseph Husslein, Bible and Labor (New York: Macmillan, 1924).

- 17 Descriptions of Husslein's

A University in Print

can be found in Joseph Husslein,A University in Print,

The Jesuit Bulletin 15 (April 1936): 1-3, 8; Joseph Husslein,A University in Print,

The Jesuit Bulletin 26 (February 1947): 12-14; William Holubowicz,University in Print: Science and Culture Series,

Sign 21 (December 1941): 281-82; William Barnaby Faherty, Better the Dream; St. Louis: University and Community, 1818-1968 (St. Louis: Saint Louis University), 298-300; and William Barnaby Faherty, Dream by the River: Two Centuries of Saint Louis Catholicism, 1766-1967 (Saint Louis: Piraeus, 1973), p. 173. - 18 Arnold Sparr describes the attempt to remedy the lack of American Catholic literature in To Promote, Defend, and Redeem: The Catholic Literary Revival and the Cultural Transformation of American Catholicism, 1920-1960 (New York: Greenwood, 1990).

- 19 Husslein

A University in Print,

The Jesuit Bulletin 15 (April 1936): 1.